Book Review: The Map of Time by Felix J. Palma (translated by Nick Caistor)

The Map of Time weaves together the stories of three 19th century London characters: a wealthy young man who loves a common prostitute, a woman who is certain she cannot enjoy life in the present, and a science fiction writer who becomes embroiled in a number of schemes. You see this? I’m practicing my gripping introductions.

I have this problem with novels in which I can never muster up the enthusiasm to write about the novels I think I’m going to write about. Then there are other novels which I have no intention of discussing that I am compelled to write about. The latter scenario is what happened with The Map of Time (and the former with The Golem and the Jinni, which I finished a week or two ago and have been contemplating since). I read The Map of Time without making a point of thinking deep thoughts about it; rather I allowed the florid Victorian prose to bear me along in its current.

For the first two sections of the novel, I was not enthralled. This is not to say I didn’t enjoy Palma’s work, but neither was I especially focused on reading it—I had to renew my loan for it twice (the library is your friend, people) although that is partly because it is a pretty long book. But once I made it to the book’s third and final part, the story came together and things became significantly more interesting. The promised map of time was revealed. Time travel conventions were explored. Threads of the story were connected. Indeed, it was art.

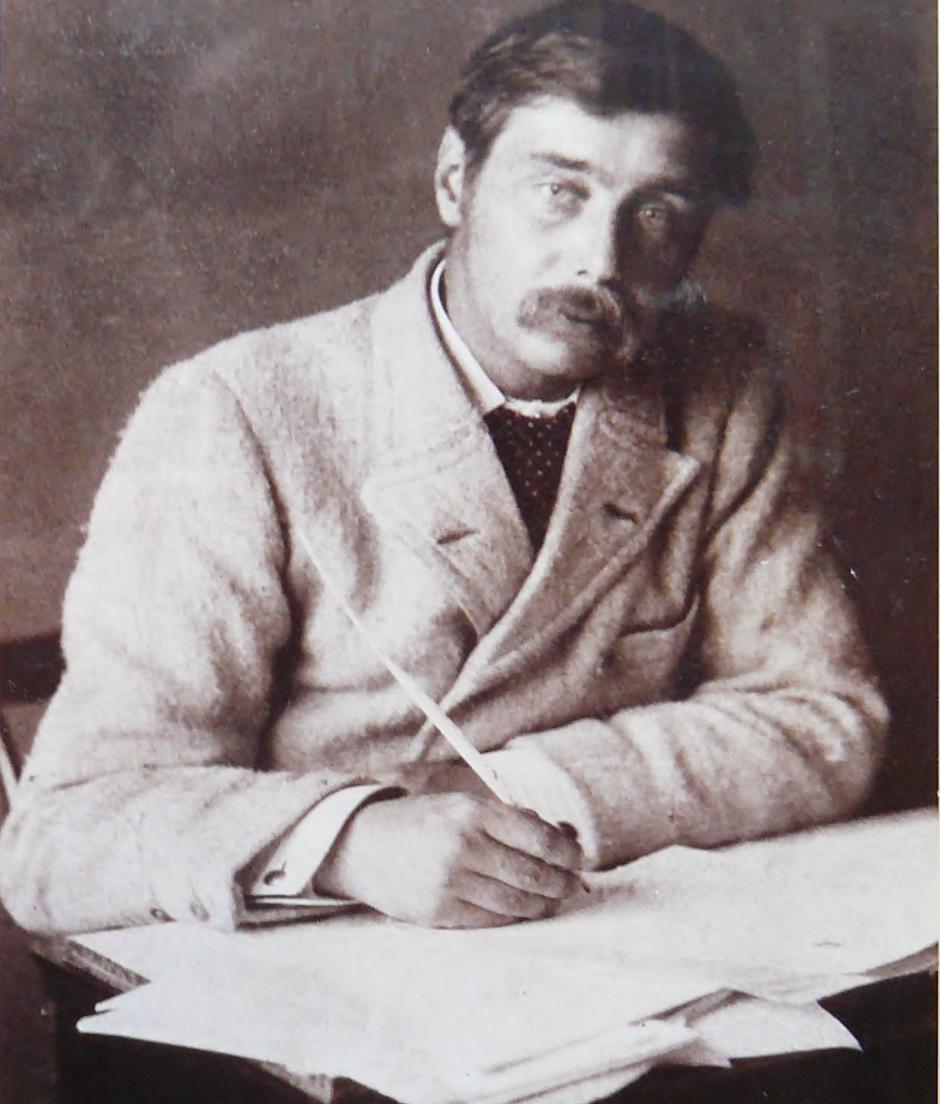

One of the things that impressed me about The Map of Time is that Palma clearly has a strong knowledge of early science fiction and the late 19th century—the novel’s setting. One of the novel’s protagonists is, in fact, H.G. Wells himself (I don’t know if any of you watch Warehouse 13, but I always want to picture Wells as a woman now, thanks to the show’s influence. Helena!). It takes skill, and a certain amount of chutzpah, to write a real person into the story. I am no Wells aficionada, but it seemed accurate (if we are to believe Wikipedia) and I felt it was well done.

This is one of those stories that is really about writers being writerly. Wells is brought into time travel schemes—hoaxes really, but for the best of causes. In both, Wells’ supplicants are seeking closure for issues in their lives. And since time travel is in the cultural zeitgeist, they believe traveling through time can really solve their problems. Why would normal people believe in time travel? In the parallel universe of the story, a man name Gilliam Murphy has opened a time travel experience in which a form of performance art is staged to make people believe they have traveled through time. Coupled with the recent popularity of Well’s The Time Machine, people begin to think that, well, anything is possible. In any case, Wells resolves his problems through, of course, writing and story telling. One involves creating a believable story for a heartsick young man. Another involves an epistolary tale told between lovers. Finally, Wells gets his due as a main character in the last section. Letters are again involved. Wells also gets the opportunity to be the subject matter expert on time travel. I think writers love nothing more than the fantasy of writing saving lives and solving problems.

I also enjoyed the way the rules of time travel were applied in the story. In the first two sections of the story, it seems like time travel is probably just a scam. No one actually time travels, but scenarios are crafted such that a number of people believe that time travel is happening. The reader gets to be in on the secret. However, in the final episode, there really is time travel, but after a novel full of fakeries, the reader hardly wants to believe it. In the end, there is some good discussion of parallel universes and such like. I quite liked where the story ended up.

The last thing I want to comment on is the quality of the translation. The Map of Time was originally written in Spanish and was later translated to English. I obviously cannot comment on the accuracy of the translation, since I have not read the Spanish edition, but the spirit of the work is amazing. I am impressed at how well the translation captures the feel of the story’s period. I can only imagine what reading this in Spanish would feel like (that’s not true, I could go find the book and then I wouldn’t have to imagine. Dear reader, you know what I mean).

Okay, I am going to keep this review a little shorter than usual, but I do recommend this book if you like things like steampunk, alternate history, the rules and conventions of time travel, or just well-researched fiction.

What to read next:

- The Map of the Sky by Felix J. Palma is the sequel to The Map of Time. It is apparently centered on Well’s The War of the Worlds in the way that The Map of Time is based around The Time Machine.

- H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life by Michael Sherborne is a biography of Wells. Reading The Map of Time, I realized I did not know that much about Wells’ life.

- Steampunk edited by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer is an anthology of steampunk-themed stories. If you like the setting of The Map of Time and have realized that you want more steampunk in your life, this short story collection should get you going.

Ever since I read

Ever since I read